The Chihuahuan Desert, dotted with prickly pear, dog cholla, blooming claret cup cactus, yucca plants, and an occasional agave plant, flashed by as Darlene and I pushed slightly over the 70 MPH speed limit. For a while, the scenery repeated itself: more peppering of shrubs, bleached hills, dry coulees, and wavering heat. Then, all of a sudden, a Welcome to Texas sign, shaped like the state itself, appeared. This was followed by a 75 MPH speed limit sign; my finger responded by clicking the cruise control up a few notches. We were well on our way to the Guadalupe Mountain National Park, following Highway 62/180 on this June 2017 morning.

Several days previously, as our plane lowered its wheels to land in Albuquerque, New Mexico, I thought to myself, I know nothing about Albuquerque. Even so, Glen Campbell’s popular song words, “By the time I make Albuquerque she will be working . . .” kept replaying in my mind. Siri on my phone, quickly provided me with many facts about Albuquerque. Among them was that famous Carlsbad Caverns National Park was nearby. I made a mental note that we should see them after we accomplished my primary mission.

“Where is the best place to see the Texas Madrones?” I had asked the ranger over the phone the previous afternoon. The McKittrick Canyon, he’d answered. He had recommended hiking up the side of the canyon, perhaps to the Pratt cabin and back, a roundtrip distance of about 4.8 miles. He’d added, “The trail is easy, and they’re about fifteen big Madrone trees growing along the way.” How young was this ranger, I wondered, trying to gauge what he meant by easy? The map showed the turn-off to be not too far ahead.

Shortly after passing a rest area with tall, blooming agave plants stippling the surrounding area, we came to the well-marked side road. Turning on to it, we were welcomed by a National Park sign and informed that we were now officially in the park. The road wound through gullies and over small rises, weaving its way along a dry creek bed as we searched for the parking lot where the hiking would begin. My heart rate began to increase; I sat up straight, now fully awake. I had been looking forward to seeing the Texas Madrone for some time. From what I had read, it should have been a lot like the Pacific Madrone, perhaps the most closely related species.

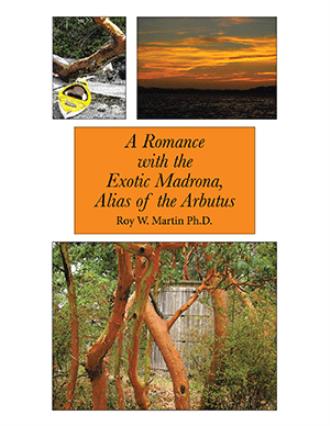

Suddenly, I brought the car to a stop. Right there on the side of the road stood a Texas Madrone. At least I thought it was; it appeared to have all the characteristics I’d read about. I jumped out of the car with my camera and approached the tree like I was stalking it. The leaves had the Arbutus look, and the canopy spread wide above. Some dead tree branches lay in front, and upright dead trunks partially obscured the lower view. However, a bare upper trunk and upper branches were visible, and the trunk was distinctly contorted. But, far from bearing the typical colors of the Pacific Madrone (green, tan, cinnamon), this tree’s bark was stark white. Maybe that is why the local name, Lady’s Legs for the Texas Madrone, arose.

First circling the tree at a distance and then moving inward, I noticed green berries, about four millimeters in diameter, distributed among the green leaves. This was to be anticipated, considering the time of year. Mixed with the tortuous white branches were also some black dead ones. I wasn’t sure if they were diseased or had died for other reasons. Brown, scalloped bark covered much of that portion of the lower trunk, which was still viable, with some dead regions interspersed throughout.

Returning to the car, we headed up the road while watching for more Madrone trees. The parking lot emerged around a corner, and abruptly we were at the head of the trail. A small visitor center was located there, a sign on the wall announcing the elevation as 5,013 feet (1,528 m). An array of display boards described the local flora and fauna. One even warned about diamondback rattlesnakes. I shivered even though, having grown up in Montana, I had the privilege of meeting them many times. I quickly steered Darlene away from that display as I didn’t want to abort our hike before it started.

A seven-minute video by Wallace Pratt told how, in 1921, he had discovered for himself the beauty of the McKittrick Canyon. He was working at that time as a geologist for Humble Oil in Pecos, Texas. One of his associates invited him on a trip to see a very beautiful place in the nearby mountains. Out of curiosity, he agreed to tag along. The two men set out across the desert despite the lack of available roads. After a few hours of monotonous travel in the hot and dusty climate, he began to doubt whether such a place existed. However, once he saw the canyon with his own eyes, he immediately fell in love with it. He later had the opportunity to buy a portion of the canyon, which was owned by the McKittricks, the same family that owned the accompanying ranch. Pratt purchased it and, after the stock market crash of 1929, was able to extend his holding to a larger area.

In 1931, he commissioned the construction of the cabin, later known as the Pratt Cabin. It was assembled primarily with rock and local wood and functioned more as a lodge than a cabin. It boasted four beds, hammocks, and a table big enough to accommodate a dozen people. It was unique. It became a summer home for the Pratt family and their guests for the next several decades. Then, in the early 1960s, the Pratts’ donated the cabin and over five thousand acres of the canyon to the National Park Service.

We headed up the trail to see the Madrones and the cabin.