Believe me when I say, many Blacks are not familiar with educational processes. Education is practically a new concept for some of us. From 1609 through 1863, most Blacks were either in slavery or in indentured servitude. In the early part of that period a few Blacks were indentured servants rather than slaves. This meant they had to serve the master for a period and were then given their freedom.

In slavery most Blacks were not allowed to read or write. If they were caught reading or writing they were maimed, killed, beaten, or sold away from whatever family they had acquired. The slave master believed that an educated slave was unfit to be a slave. Some slaves did learn to read and write as well as do simple mathematical calculations. They either learned from the slave mistress or were taught by other slaves. If a slave was fortunate to get some education, he or she did so usually without the slave master’s knowledge. The slave master’s objective was to keep the slave from getting even a minimal education.

After the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, some Blacks were able to attend schools that were sponsored by private church groups, some schools were available through the government, but even then, there were few schools available. Schools were few and far between. Most of what was available consisted of one-room schoolhouses, with a potbellied stove for heat. It was usually cold in winter and hot in summer. The children in many cases took turns chopping wood during the winter months. Materials, books, and supplies were limited. Most of it was outdated and passed down from the larger part of the district when no longer useable. In the early years of the Emancipation, some teachers in Black schools were not college educated, even in the 1940s and 1950s. James Meredith, who integrated Ole Miss, says that he never had a teacher with a college education during his twelve years of school. We were supplied with inferior teachers generated through this inferior system. Inferior teachers can only produce mostly inferior students. This assured the maintenance of an inferior system. It’s not necessary to denigrate our teachers, for without a doubt many of them did the best they could with what they had. Some of the students had to walk for miles without any kind of transportation just to get some semblance of an education; sometimes having the white bus pass them on their way. Some children in rural areas lived too far from school and there was no transportation. Many didn’t have access to any form of education, but some were able to get an education even though it might have been inadequate. Most rural areas didn’t have high schools, and if a student didn’t live in the city could only get an elementary education. I’ve also read about and heard older individuals talk about how they had no buses to take them to school. One individual talked about how the white bus would frequently pass them on the road and intentionally taunt and splash mud on them.

Too many individuals had to quit school early to work on the plantation. At many schools the year would not run for the full nine months, because the students were needed on the plantation. Schools frequently dismissed early during the day to accommodate plantation work. Such negative conditions continued to some degree in many places until the 1960s.

This situation remained for many years. When we finally began to get schools for Blacks the system still undereducated them. The system made sure Blacks had a poor quality of education. The educational system left us unemployed, dependent, and a drain on the economy.

During the early and middle parts of the twentieth century many Blacks were practically still attending that one-room schoolhouse. Again, many Black children got time off from school to work in the fields. Supplies, books, and materials as well as infrastructure were inadequate to those of whites. Things did improve during the latter part of the twentieth century: the government began to be more responsible for universal education. School buildings did begin to improve. Most of the funds were usually funneled off to the larger part of the district. More money was allocated for white education than for Black education. Some Black schools still had plaster falling from the walls, and they leaked when it rained. Many of the buildings were in much need of repair. I visited a Black school on the south side of Chicago in 1987, and rats were playing in the middle of the floor as if they owned the building. This should have been a source of embarrassment to the people in charge, but they seem to regard it as normal. Integration finally came during the 1960s. With Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, things got a little better. With the threat of integration, the people in authority decided to try and pacify the problem, by building completely new Black schools rather than integrating. Some schools did integrate, but most of them went on with business as usual. Many Blacks were allowed to attend integrated schools, but never at the level they should have. There was also the question of how comfortable these settings made Blacks feel, and whether the attitudes of whites served to further denigrate the self-esteem of Blacks.

There were several major obstacles to integration. Probably the biggest hurdle was the concept of the neighborhood school and objection to bussing. This caused integration to never realize its full potential. Integration is still prevalent in schools where Blacks and whites live in the same district.

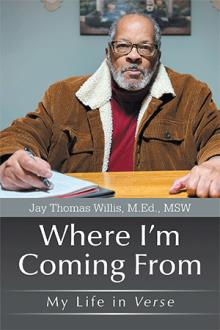

Check out this and other of my books @ www.willisjay.com, by Jay Thomas Willis.

Jay Thomas Willis

Richton Park, Illinois