How Long is Exile?

BOOK III The Long Road Home

by

Book Details

About the Book

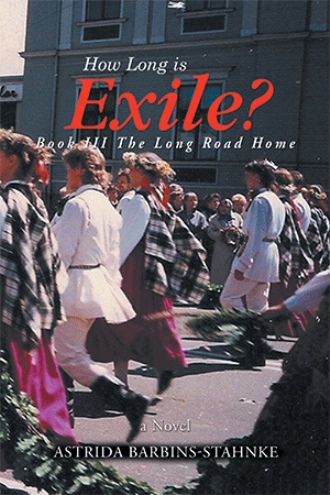

At the end of Book I How Long is Exile? — The Song and Dance Festival of Free Latvians — widowed Milda Arājs had taken a new direction in her life. She had decided to break solidarity with her mainstream ethnic community and make good her promise to her daughter Ilga that they would make a "pilgrimage" to Soviet Latvia at Christmas time (1983) and welcome the baby Krišjānis, born to American Māra and Latvian Igors, as the symbol of a new era. Also, Milda had chosen to give herself to Pēteris Vanags, the one-armed veteran she encountered in the Esslingen DP camp after the war. (Story in Book II—Out of the Ruins of Germany.) They married shortly before the momentous trip, and soon thereafter Milda joined him in Washington, D.C. For a decade they lived happily, making up for lost years of forbidden longing and desire—until the Soviet Union fell, and the Kingdom of Exile felt the shocks and afershocks.

Unbeknown to herself, Milda's Christmas trip behind the Iron Curtain, with all its revalations, was her first step on her Long Road Home. Also, that trip at the height of American women's liberation movement, marked her adult coming of age and becoming the ruler of her life. Released from domestic bonds, she struck out on her own and challenged her mind to higher things. When Peter, in the late 1980s, was asked to join Radio Free Europe in Munich, Milda saw her Road clearly winding its way back to Latvia. This, naturally threatened the marriage. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, the Road become bumpy, even trecherous. Afraid and out of step, Peter seemed to lag behind, while Milda hurried forward now that the iron curtain was swept away. With firm steps she returned to her homeland; she reunited with her sister Zelda and reclaimed their parents' apartment. Peter complied and came up with the money, but, as if lost, he often went off by himself, afraid of being watched and pursued until he could not walk anymore. After his death and after the guarded secrets were revealed, Milda took her last steps on The Long Road Home alone.

Exile was over, but the sense of exile was imbedded in Milda's mind forever, and it was heavy. She felt the weight most poignantly as she watched fireworks grace the skies at elaborate festivals, where strangers celebrated, frolicking and singing to her unknown songs, and young people rush about in search for passages to new lands, where the grass seemed greener and fame and fortune beckened from clouds with silver linings.

As a participant in that, so called exile state, I began writing my version of the experience after the Milwaukee festival, filtering it through the consciousness of my main character Milda Bērziņa-Arājs, who, coming out of mourning for her husband Kārlis Arājs, arrives at the festival, ready to turn a new leaf in her life. During the four days with like-minded people, interesting events, and common recollections of her childhood, the war and post-war experiences in a displaced persons' camp flash before her in a swirling kaleidescope and, at the end, throws her in the direction she did not plan to go.

Book II captures the mood after the fall of the USSR. The ethnic communities—the Kingdom of Exile—is shaken, and the people awake as if from a deep sleep. Milda suddenly becomes active; she makes crucial decisions and switches from an outdated romantic into a realist as she returns home, meets her estranged sister and the country she had left behind. As she tries to find her place in it, she understands that exile is a state of mind; it is a state where half the world's population lives—like she—uprooted by tyranny and wars. Yet she and other displaced persons go on living and finding pleasure in art, poetry, song, and in each other—though with a sad, melancholy smile.

About the Author

I was born on March 15, 1935, in Priekule, Latvia, to Rev. Juris and Milda Barbins, the fourth of six children. I greatly admired my mother, a graduate of Latvia University's English Institute for her quiet wisdom and love for us. My father, a Baptist minister, served several country churches in Kurzeme, often taking us all along in our horse-drawn droshka. It was on those trips and other excursion where, early in life, I learned to love my native, pastoral landscape and the stories of the Bible, for at a very early age I too was a little shepherdess and many times had to look out for the wolfs that frightened my lambs.

Our family's days on the farm, with its sunshine and dark clouds, ended on Sunday morning, October 8, 1944, when the German and Russian armies were at our borders. We had two hours time to escape, which we did in our horse-drawn wagon. Suddenly we were six homeless refugees. (My youngest brother had died, and my oldest brother was in the Latvian army.)

Until the end of the war, we traveled through bombed-out Germany. When the war was over, we found ourselves in the American Zone, in Esslingen, in a Displaced Persons' (DP) camp, where we lived until we emigrated to the United States, in August 1949. After living a year in Charlotte, N. C., we re-located in Cleveland, Ohio, where my father formed a church and helped to establish the Latvian Community.

After graduating from Shaw High School, I attended Western Reserve University for a year and then went on to Bethel College in St. Paul, Minnesota. By then, having sufficiently mastered the English language, I decided to major in English and study literature. That opened exciting worlds of the spirit and, inevitably lead to writing and my first award. At Bethel I met my husband, Arthur Alan Stahnke. We were married September 6, 1958. With that I left the Latvian community, eager to go on with my life as an American.

By the time my husband received his PhD and obtained a tenured position as professor of political science at the newly opened Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville (1963), we had two children and a house. Feeling restless, I enrolled at the university and completed my BA in 1969, before our fourth child was born. When he went off to school, so did I and enrolled in the SIU-E English department's graduate school and gained my MA in 1977 in English and comparative literature. I wrote my thesis about a Latvian female poet and playwright Aspazija (pseudo. Elza Rozenberg, 1865-1943) whose romantic tragedy Sidraba šķidrauts (The Silver Veil), 1905, I had translated as participant in the SIU-Carbondale Translation Project.

Excited about the play and its author, I decided it was time to return to my roots, and I flew back to Latvia, which then was locked behind the Iron Curtain. That was a profound turning point in my life, as I embraced my true identity from which I had tried to escape. My purpose in life (outside the family, which I would never abandon) was clear: I had to continue translating and bring the Communist-oppressed fantastic writer in the English-speaking world and I had to write my country's story. It would answer the frequently asked question, where you from? And so, as life changed, my parents aged and died, and we the siblings also aged and our children grew up and left home, I was busy translating and simultaneously writing poems, stories, articles (published in ethnic press) and working on How Long is Exile? When my husband received a Fulbright stipend to study in East Berlin, I accompanied him part of the time and revisited the places our family had lived during the war and after. All that gave me rich source material for the novel. Now when my country is free, I make regular trips home to visit my Siberia-surviving brother as well as the intellectual community that has rehabilitated the once politically incorrect national writers, including Aspazija.

My latest trip back was in March 2015, when Aspazija's 150th birthday anniversary was celebrated with great pomp, including an international conference where I was invited to speak (April 15–18). The event gave me great joy as it coincided with my birthday and came as a reward for all the translating and writing I had done on her behalf. Together, we had put Aspazija back among important 19th/20th century European writers. My book Aspazija's Prose, which came out in Latvia, at the end of March, had its presentation at my surprise birthday party at the immortal writer's house in Jurmala. The event, with flowers, music, and poetry was a crowning experience. It is indeed a gift of heaven to see my country free again and see many dreams come true. The last trip marked the end of another stage in my life. Now I look forward to the publication of my two-book novel How Long is Exile?